A commentary on the Historical, Cultural and Local Significance of Ormskirk Parish Church

Ormskirk Parish Church from the South

Ormskirk Parish Church – North Elevation and basic ground plan

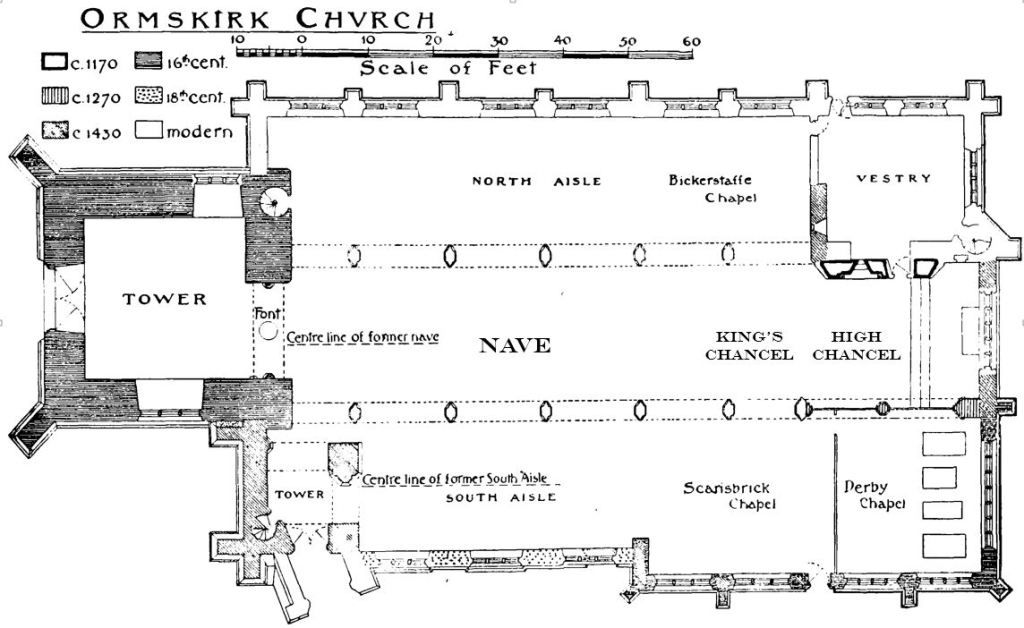

Sketch-plan of church for reference, although not entirely accurate and dating of masonry similarly inaccurate

Ormskirk Parish Church is a large parish church with a wide nave, covering a footprint of some 1000m2. It is set on a solid rock outcrop at an altitude of some 80m above the South-West Lancashire Plain. The earliest extant parts of the structure are of Norman origin (not later than 1189) although there is evidence of a Saxon church previously on the site.

Possible re-use of Saxon Cross-Shaft in east wall

It is unique among English churches in having a tower and a spire adjacent to each other, both at the west end.

As a result of this unique characteristic, and being the oldest standing building in the area, it forms the symbol of West Lancashire, and is included in the coat-of-arms of the Borough.

There is an ancient and now discredited legend around the origins of this feature, involving the two daughters of Orme, the Viking founder of the town (and of the church – Orm’s kirk), in around AD 840, who wanted different features and arrived at a compromise. This legend spawned a rather derogatory limerick by Spike Milligan:

A lady in Lancs said a spire

Is what every good church should desire;

But her sis, with a glower

Said a church needs a tower,

So they built one with both, and it’s dire!

The commonly-accepted view is that the steeple (i.e., the tower with spire) dates from around 1430 and that the great west tower was built over a century later, to accommodate the bells from Burscough Priory following its dissolution in 1536. This story, predicated on a will of 1542 when £60 was left for (among other things) ‘the building of the steeple and church of Ormskirk’, seems to have been accepted by ‘historians’ (even including Nikolaus Pevsner) although recent more detailed examination by conservation architects now seems to concur that the great west tower is, in fact, more likely to be a development of an earlier defensive tower, possibly of Norman origin, substantiated by a number of very convincing pieces of more detailed architectural evidence.

Returning to the spire, a sanctus bell was hung in it, in 1521, by the 2nd Earl of Derby, and remains in situ to this day. That bell has a rope into the church, enabling it to be rung to indicate the consecration of the elements during the Roman Mass, as this date places it before the Reformation and change to Protestantism.

The Sanctus Bell in the Octagon of the spire

Of the bells from the former priory, only four were brought to Ormskirk; the original Tenor bell now sits on a wooden plinth in the Bickerstaffe Chapel, and is dated on its casting at 1497. in 1948, it was replaced by a new tenor and the remains of the full ring (which had grown to 8 bells) recast.

Date casting (1497) on the former Tenor Bell from Burscough Priory. Note the portcullis (for the Beaufort family) and the Tudor Rose and Fleur-de-lys (for the Crown)

The church encompasses architecture across the intervening centuries, through to the present.

The Norman wall with window, in the north of the chancel, forms the base of the present organ loft. The window was discovered at the time of the restoration of the church, which took place between 1877 and 1891; it had previously been boarded and plastered over, presumably during the 1729 ‘classicisation’.

The Norman window in the north wall of the High Chancel; below; the C13 arcade in the south chancel wall, showing its C16 upper extension on the building of the Derby Chapel

The south chancel arcade appears to date from c.1280, and previously opened into a smaller chapel than now; most likely a Lady Chapel. On the other side, there is still evidence of the use of lime-wash, which defines the height of the arcade prior to the development of the present Derby Chapel, which was constructed between 1574 and 1579, when the roof level was raised, as evidenced by the increased height of stonework evident. On the chancel side of the same wall, above the 1280 arcade, yet another tier of stonework is evident as the ancient wall was raised again, to accommodate a higher chancel roof on the restoration.

In the north aisle wall, completely rebuilt in the late C19, are set two pieces of masonry dating from an earlier epoch; one appears to be the label-stop of a hood-mould and the other, the base of a pier predating the Georgian work removed at that time.

(Above and below) Older masonry incorporated into the wall of the North Aisle

In many ways, the Victorian ‘restoration’ was just that; the architects, Paley & Austin of Lancaster, paid attention to what they found of the pre-1731 building during the demolition and removal of the by-then-dilapidated Georgian work. For example, the width of the bays at the east end of the north and south nave arcades differs, the one from the other, reflecting the pier foundations which Paly & Austin discovered when the burials under the previous earthen-floored nave were exhumed and re-interred outside. However, the burials in vaults under the chancel, Bickerstaffe, Derby and Scarisbrick Chapels were allowed to remain, the vault under the Derby Chapel having been bricked over and closed in 1851, when the Earls of Derby moved all subsequent burials to Knowsley.

The remaining C18 parapet to the south aisle

The sundial in the churchyard

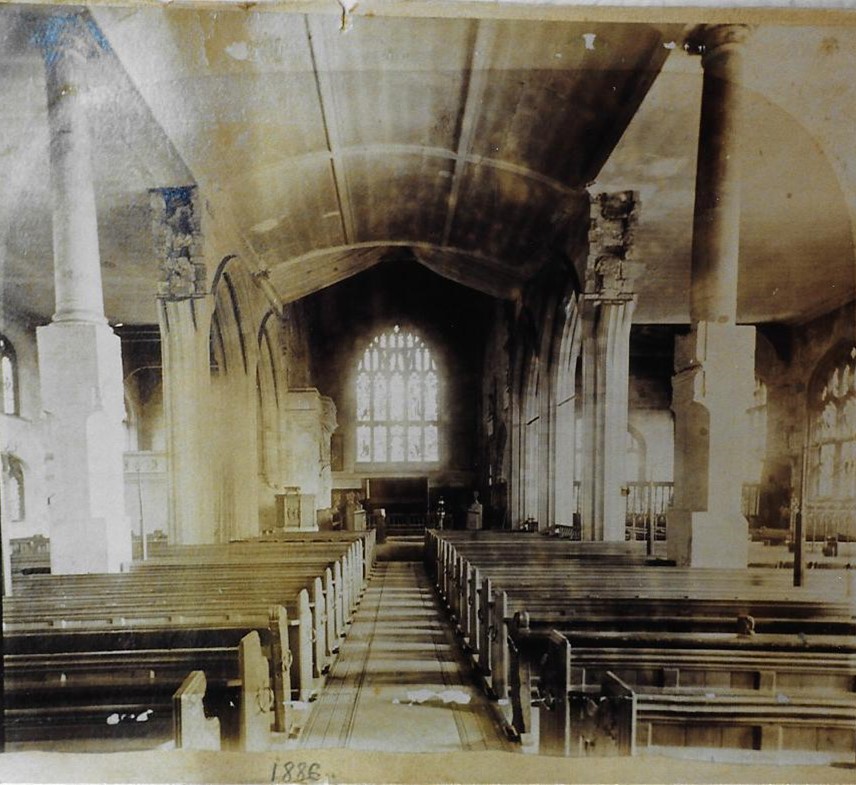

View of the C18 nave after the removal of the north and south galleries

During the replacement of the classical columns and roof

Effigies of St Peter and St Paul at the junction of the C19 work and the pre-existing chancel walls

The architectural anomalies to be found in the building pose more questions than they answer; for example, there are no clear centre-lines for the nave, chancel or south aisle. Only the north aisle has any uniformity, as it is the construction of Paley and Austin from the 1890’s, when it was discovered that the old north wall had no proper foundations and had to be completely rebuilt.

The fabric of the church, then is of major significance regarding the history not only of the building itself, but of the social history of the town. This deserves to be flagged up to the general public who have little, if any, knowledge of its antiquity.

The monuments in the building are of great significance, as well. The north and south walls of the nave, where they meet the chancel, reveal ancient niches containing the figures of St Peter and St Paul, the patron saints of the church.

The Eagle and Child, being the crest on the heraldic achievement of the Stanley family, now Earls of Derby, on the wall of the Derby Chapel

High on the walls over the ‘King’s Chancel’, so named because it was here that King Henry VII and his court worshipped whilst staying with his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, 1st Countess of Derby, in 1495. Also to be found are the Tudor Rose and the Portcullis, being allusions to the Tudor dynasty and the Beaufort family, whose device was the portcullis.

In the Derby Chapel, on the wall will be found the Eagle and Child, which forms the crest of the heraldic achievement of the Stanley family.

That motif is repeated by the design of the weather-vane atop the spire. One branch of this family was ennobled to become the Earls of Derby after their part in securing the overthrow of Richard III, and subsequent crowning of Henry VII on the battlefield at Bosworth. At that time, however, Stanley burials were still taking place at Burscough Priory and it was only after the dissolution that burials and memorials of the Lords Stanley and the Earls of Derby were removed to Ormskirk. The four recumbent alabaster effigies in the Derby Chapel date from this move; they represent the First Earl of Derby, his first wife, Eleanor Neville (sister of the Earl of Warwick, ‘The Kingmaker’), his second wife, Lady Margaret Beaufort, and Sir Thomas Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley (created 1456).

(Above) Effigies of Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby, and Lady Margaret Beaufort, his second wife and 1st Countess of Derby (moved here from Burscough Priory at the Dissolution)

(Below) Effigies of Eleanor Neville, Lady Stanley, first wife of Sir Thomas Stanley, and her father-in-law, (also Thomas Stanley), 1st Baron Stanley

Buried in the vault beneath the Derby Chapel are the remains of many members of that family, including those of the 7th Earl, buried in two coffins following his execution by Cromwell’s forces at Bolton, and his wife, Charlotte de la Tremoillé, who had held Lathom House during the siege of 1644/45.

Two chest-tombs, originally from the Bickerstaffe Chapel, whilst now bereft of their brasses, still provide evidence of many other members of the Stanley family from across the north-west, in the painted shields around their sides. The colouring, although much faded, is still discernible. Luckily, they were recorded, whilst in better condition, in drawings by Sir William Dugdale in 1664.

The two tomb-chests acting as memorials to many filial branches of the Stanley family, represented by their surrounding coats-of-arms

In the Scarisbrick chapel is a large brass memorial which would seem to be that of Henry de Scarisbrick, who fought alongside Henry V in 1415 at Agincourt, for which he was knighted. Originally from Burscough Priory, this was found under the floor of the Scarisbrick Chapel at the time of the Victorian restoration. It begs the question of what else might be waiting to be discovered!

Memorial Brass to Henry (Stanley) de Scarisbrick, who fought alongside Henry V at Agincourt

There are smaller brasses on the walls, one of which (the ‘Mosoke Brass’) is dated 1661 and claims that the donor’s ancestors have been buried there since 1276.

There are C17 wooden screens surrounding the Derby Chapel, surmounted by metal pikes. This door is set into the screen enclosing the west and north sides of the Derby Chapel

Within the church are some remaining apparently late Elizabethan bench-ends; in most cases, the benches joining them have been replaced by more modern work but in a few cases, the entire C16 benches remain intact. One such is the dog-whipper’s pew, complete with drawer for the whip.

The Dog-Whipper’s pew and one of the other surviving ancient bench ends, which are late Elizabethan, from the re-pewing of the church in 1593

The font, dated 1661, with the ‘C II R’ cypher, was given by the Countess of Derby to commemorate the Restoration of the Monarchy with the accession of Charles II.

The hexagonal font bowl, dated 1661, with the ‘CIIR’ cypher

The altar which was part of the church prior to the C19 ‘restoration’, dating from 1693, towards the end of the rule of William II and Mary II, is presently stored in New Church House.

The previous (1693) altar, now in New Church House

In terms of more contemporary work, there are five chandeliers and a matching, suspended, font cover by George G Pace, dating from the 1970s.

The 1970’s chandeliers by George G Pace; of these, there are four in the nave and one in the Derby Chapel; there is also a matching suspended font-cover

A glazed screen, separating the tower from the nave, appears also to be by the same architect. In fact, around the same time, Pace drew up plans for an extension at the north-west end of the church, which would have formed an attached parish hall, but this was never enacted.

We are committed to celebrating the work throughout the centuries which has amalgamated to form what we have today, whilst seeking to further develop the building to return it to its roots as a centre of community activity.

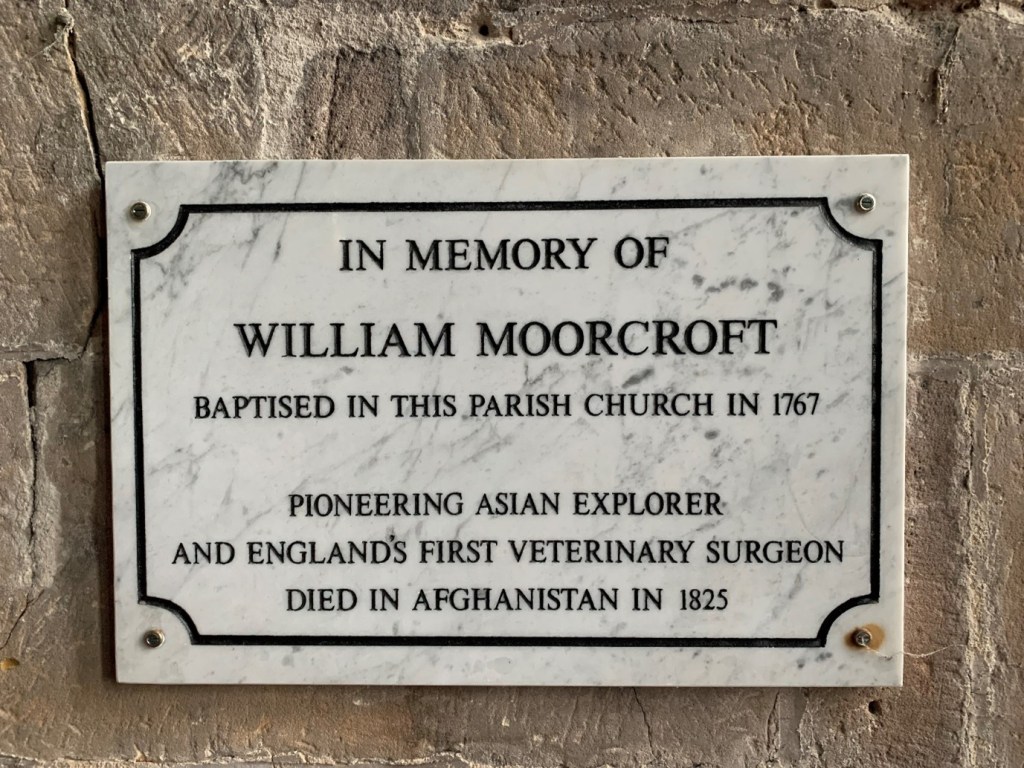

At the west end of the nave is a relatively modern memorial to Britain’s first veterinary surgeon, William Moorcroft, who was born here in 1762 and was sponsored by local landowners to abandon his medical training and go to the veterinary college in Lyon, due to the need for someone who could treat farm animals during epidemics which were decimating the pastoral population. He set up the first British Veterinary practice in 1797 eventually opening a society practice in Regent Street, London. Moorcroft later became a pioneer explorer and worked with the East India Company, in which capacity he died, in 1825.

The memorial to William Moorcroft. A similar memorial referring to him as ‘the famous traveller, William Moorcroft’ graces the wall in a pavilion, built by Ranjit Singh, the so-called ‘Lion of the Punjab’ in the Shalimar Gardens, Lahore, where he stayed during his visit to the court of that first Sikh Maharajah in May, 1820

In the churchyard are a large number of poor graves, i.e., mass graves of those from the poor-houses, not only in the immediate area but also from further afield, including the poor of Huyton, Litherland, Thornton, UpHolland, Knowsley, Bootle and Bretherton, amongst others. Some of the stones recording these were stolen from the churchyard in 2023. A project to study the significance of these is currently on-going.

Also of historical significance, are two other elements in the church which are significant in their own ways, although not, strictly speaking, part of the building.

Firstly, abutting the smaller of the two towers, and outside, is a Victorian cast-iron urinal, recently restored (although not in use for its original purpose!).

Secondly, the organ. It was uncommon for parish churches to have organs to accompany worship before the Victorian era. However, Ormskirk had an organ recorded in 1552, which was (fortuitously) dismantled and stored in the tower during the Protectorate. At that time, with organs being destroyed by Cromwell’s vandals, organ-builders emigrated to France and Germany, where their skills were still appreciated. It took some time after the Restoration of the Monarchy for them to return and even then, only two did; it was from the work of these two craftsmen and their successors that all others learned their trade. Ormskirk decided to invest in an organ in 1729 and the present instrument is descended from that. In terms of number of pipes (3356), it remains the largest musical instrument in a church (i.e., not a cathedral) in the counties of Lancashire, Manchester and Merseyside. The organ-builder engaged at the time was one William Denman of York; it was his magnum opus, with much, if not all, of the new pipework probably supplied to him by Norman & Beard of Norwich, who were, then, the largest suppliers of such things in Europe. The late Noel Mander, the noted organ-builder and historiographer, who was responsible for the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral organ in the 1970’s, said of Denman, “A very clever mechanic. Each piece of action most carefully made and as good today as the day it was put in.” In fact, although a few additions were made at a rebuild in 1927, at the time of its building in its present location, in 1894, it was larger than a number of cathedral organs, including St Paul’s. The significance of this is one of social development; during Victorian times, organs were seen as a measure of civic pride and success, so Ormskirk’s possession of something of this calibre was a major coup for the town.

It is therefore evident that the building contains many points of historical significance, as well as having been a focal point for the town and its related social history, throughout its span of a thousand years. It is, in our view, essential that this is preserved for future generations, in order to chronicle the changing needs of the population and their part in the Wars of the Roses and also the English Civil War, and the area’s importance within the context of the Dukedom and County Palatine of Lancaster.